The Spectrum Singers: Farewell to Music Director John Ehrlich

Tagged:Beauty

/

MeaCulpa

/

Religion

/

TheDivineMadness

Saturday, we went to a concert by the Spectrum Singers in Cambridge, at the historic First Church Congregational. I was a little apprehensive about Schoenberg and Ives, but looked forward to the Vaughan Williams.

The Occasion

The Spectrum Singers is a very high-quality choral

group, well known in Cambridge for many years. They’re occasionally described as “hip

classical”, or invoking the word “spectrum” to describe the broad range of the choral

repertoire they explore – from early music to the 20th century. (Though, barbarian

that I am, I always mis-hear it as “Spectral Singers” and think about a choir of ghosts.)

The Spectrum Singers is a very high-quality choral

group, well known in Cambridge for many years. They’re occasionally described as “hip

classical”, or invoking the word “spectrum” to describe the broad range of the choral

repertoire they explore – from early music to the 20th century. (Though, barbarian

that I am, I always mis-hear it as “Spectral Singers” and think about a choir of ghosts.)

Recently John Ehrlich, their music director for the last 44 years, decided to retire. In various talks, he’s described his motivation as making sure Spectrum Singers didn’t become the John Ehrlich Singers. The venerable Globe [1] has the goods.

The Venue

Traditionally the venue for Spectrum Singers is

First Church Congregational, in Cambridge.

(Other musical organizations performing there are the Boston Early Music Festival,

the Cantata Singers, the

Seraphim Singers, and others.

Traditionally the venue for Spectrum Singers is

First Church Congregational, in Cambridge.

(Other musical organizations performing there are the Boston Early Music Festival,

the Cantata Singers, the

Seraphim Singers, and others.

Congregational churches (now UCC) have a deep history in New England, and indeed are the denomination of my youth. While this congregation goes back to 1633, the current building dates to 1872. This photo, from their web site, shows the interior of the worship space. It is architecturally reminiscent of a cathedral, with transept and nave as shown here.

- A number of the stained-glass windows are Tiffany originals. Given the date, they were buying from Tiffany before that became a really big deal, so these are early works. Alas, we were there at night, so the lighting was suboptimal for enjoying the windows.

- The arches around the transept/nave/bema are all curiously 7-sided. There’s usually some significance to things like that, but the symbolism of 7 escapes me.

- You can see some medallions in the spandrels at the top of the arches. The marginal vision of my now-ancient eyes makes them difficult to make out in detail. But some glaring at them after the concert seems to have revealed that one was a capital Α/Ω motif and the other a capital Χ. Given the Congregational history, they of course makes sense as Christological symbols.

So it’s basically a beautiful old building: about 150 years as a physical construct, and about 400 years as a social one. Needless to say, every single thing you see is crafted to make you think about deeper meanings. (There are, of course, anachronisms that are inevitable in any building remodeled for comfortable modern use. For example, there are electrical outlets at the top of each pillar, just above the Corinthian capitals. That caused me to smile a couple times, because I love the fact that it’s both anachronistic and that it shows the determination people have to continue using the building comfortably.)

The Program

A pre-concert lecture by Steve Ledbetter was quite informative, telling us a bit about each of the composers as people, not just as musical giants. I have a soft spot in my heart (and possibly in my skull) for trying to regard people as fully-formed human beings, not just as the source of whatever work they did. People are not instrumental goals, we are end goals in ourselves.

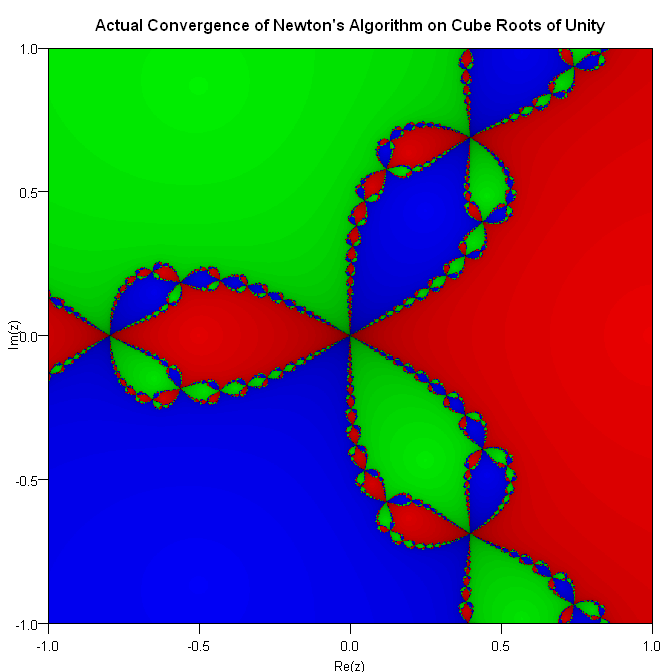

Charles Ives, for example, was also an actuary (Math Tribe! Math Tribe! Math Tribe!) and invented a lot of the business practices in modern insurance, such as insurance for estate planning. Given his love of dissonance in music, it seems only apt that his spouse was named Harmony.

Upon taking our seats, it struck me that… well, as you can see here, they certainly

didn’t waste money on any fancy-pants printing of the tickets! (Though, to be sure, in

the modern American political parlance, I am a left-wing voter in a blue state, so “BLUE

LEFT” is ironically apt.)

Upon taking our seats, it struck me that… well, as you can see here, they certainly

didn’t waste money on any fancy-pants printing of the tickets! (Though, to be sure, in

the modern American political parlance, I am a left-wing voter in a blue state, so “BLUE

LEFT” is ironically apt.)

Yes, it’s a small thing. It still amuses me, though, in a frugal New Englander sort of way. Be proud of the music, don’t worry about the rest. Good job there, with unpretentious tickets.

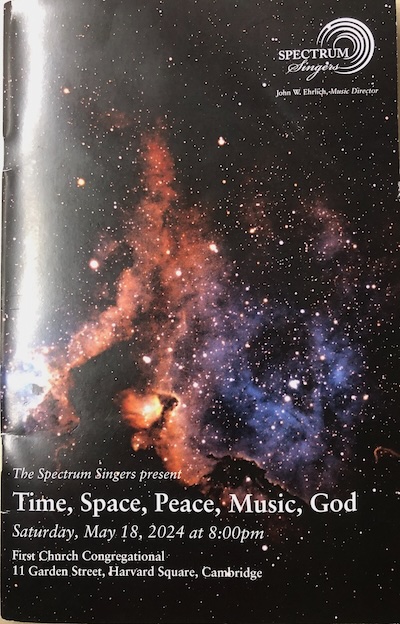

Now, the program, on the other hand… you can’t call your concert “Time, Space, Peace, Music, God” and not be a little bit pretentious! (I don’t quite recognize the astrophotography, and the program itself carefully avoids giving credit.)

But… when you look over the pieces, they are also cosmic, almost in the sense of old-style Russian Cosmism, seeing the divine in the ordinary and the human.

None of the composers would agree that was their inspiration, and musicologists would just laugh at the comparison. Still, it seemed to me that finding the extraordinary in the ordinary is a useful skill. Almost anything is interesting, if examined closely enough. (And that may well be the theme of this Crummy Little Blog That Nobody Reads (CLBTNR).)

The pieces in the program shown here, while definitely not all to my personal taste, nonetheless are consumed with beauty and loss, followed by the hope for better days, better lives, and better spirits. They’re each… odd. Schoenberg chose to write a dissonant piece for a text about forming peace. Whitman was… well, just being Whitman is enough, isn’t it? Vaughan Williams was a welcome balm for the brain, after the more dissonant pieces preceding him.

All these composers were alive at approximately the same time, at least overlapping to some degree, writing 1907 - 1938. It always surprises me to be reminded the degree to which World War I absolutely shocked and scarred the world. (Indeed, in 1923 Schoenberg wrote to a friend that he no longer thought world peace could be possible.) Today, having survived World War II and numerous lesser – but even more pointlessly brutal – conflicts, we tend to underestimate that. People wondered how it could even be possible to return to normalcy, in a world where “normal” seemed to have been utterly mutilated.

Still, as we previously wrote on this CLBTNR, artists responded in sometimes encouraging ways, as with WH Auden’s “September 1, 1939”. Perhaps, like these composers, we need to learn to “show an affirming flame” in these fascism-darkened times.

The Pieces

Let’s go through the program and think about what we heard and read.

Schoenberg: Friede auf Erden (1907)

What can one say about Arnold Schoenberg?

You either love his music or hate it, and I am not numbered among those who love it.

Dissonance is not my main drag. 12-tone is annoyingly incomprehensible. (With probably 1

exception: mathemusician (self-yclept) Vi Hart’s magisterial and hilarious tutorial

video, shown here. [2])

What can one say about Arnold Schoenberg?

You either love his music or hate it, and I am not numbered among those who love it.

Dissonance is not my main drag. 12-tone is annoyingly incomprehensible. (With probably 1

exception: mathemusician (self-yclept) Vi Hart’s magisterial and hilarious tutorial

video, shown here. [2])

Yes, this betrays me as remarkably unsophisticated. (Just to seal your low opinion of my low taste, I don’t care for jazz, either.) In Japanese, I am a ダサい 野蛮人 (dasai yabanjin, approximately “uncool barbarian”). Yes, mea culpa. Mea maxima culpa.

Just listening to Schoenberg, without context, is for me approximately like having acid

dripped slowly into my skull. Fortunately, that was not the case here: we were in a beautifully

contemplative setting and there was a poem being set that I could appreciate.

He chose a difficult poem by Swiss poet Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, “Friede auf Erden” (“Peace

on Earth”). The excellent translation in the notes was by

Bernie Greenberg, my former

colleague in the old days at Symbolics.

In Ehrlich’s own program notes, he describes it as:

Schoenberg’s thorny, conflicted yet cautiously optimistic plea for peace now seems all-too appropriate for our presently fraught times…

So… it began with relative harmony, but then the usual acid begin slowly dripping into my skull. However – and this is really saying something – the text completely redeemed the experience for me.

Meyer’s poem, in Bernie’s skillful translation, echoed the frustration, dread, and anxiety felt by all of us without power, when we watch those with power stumble clumsily but determinedly toward fascism and cruelty:

Yet survives belief eternal

that the weak shall not forever

fall as helpless victims to each

murd’rer’ fresh indignity.

Righteousness, or something kin,

weaves and works in

rout and horror,

and a kingdom yet shall rise up

seeking Peace upon the Earth.

The idea that chaos and evil are the necessary soil in which righteousness can grow is uncomfortably familiar. So the Schoenbergian dissonance actually works for me (much to my surprise!) as a way of describing the painful chaos in the world.

Toward the end, it becomes more harmonic in D-major, when Meyer’s poem – like all good Psalms – visualizes a more perfected world:

Slowly shall its form develop,

holy duties while fulfilling,

weapons free of danger forging,

flaming swords for cause of Right.

And a royal line shall bloom,

mighty royal sons shall flourish,

whose bright trumpets peal

proclaiming,

Peace, O Peace upon the Earth!

I absolutely love the idea of turning “weapons of war” on its head as a metaphor, so we forge ‘weapons’ free of danger, like flaming swords that do only good.

It’s a reminder, mildly painful in a good way, of a piece in CS Lewis’s The Great Divorce [3], another work written in the context of a Great War, like the other pieces in this concert. I’m not normally a big fan of Lewis. He appeals to fundamentalists for some reason, and that’s probably why he does not appeal to me. For The Great Divorce (and his lecture, “On Transposition”), I make exceptions. They are both really mind-changing for me.

In The Great Divorce (chapter 11) there is a scene where a man has a lizard on his shoulder, representing his sinful nature. An angel offers to kill it with burning hands (reminiscent, at least, of a flaming sword). In the end, he does this. The man becomes more perfected, and the lizard becomes a horse which he rides into deeper heaven.

The moral, apparently, is that our sins are energy in need of redirection.

That is the sort of weapon I would cheerfully help to forge. And only that: the flaming sword becomes less of a weapon to hurt, and more of a scalpel to heal. The thought of it actually makes Schoenberg’s harmony-dissonance-harmony journey worth taking.

Vaughan Williams: Towards the Unknown Region (1906)

After the harmonically bruising experience of Schoenberg, we need some healing balm. I

remarked to a friend who is in the Spectrum Singers, that there’s a reason

Ralph Vaughan Williams pieces

immediately followed Schoenberg and Ives.

After the harmonically bruising experience of Schoenberg, we need some healing balm. I

remarked to a friend who is in the Spectrum Singers, that there’s a reason

Ralph Vaughan Williams pieces

immediately followed Schoenberg and Ives.

This piece is based on Walt Whitman’s poem “Towards the Unknown Region”, aka “Darest Thou Now O Soul”, from Leaves of Grass (1881-1882). (NB: The program notes say “Toward”, but apparently Whitman wrote “Towards”. I will now stifle my inner pedant.)

Now we’re breaking out the heavy artillery! US Republicans are currently engaged in a book-banning spree against allegedly dangerous books. Of course they pick the wrong books! And they have no appreciation of just how wonderfully dangerous some books are, and why that is A Good Thing.

Reading as a young man, Whitman wounded me in a way that will never heal, and which I will never want to heal. Apparently Ralph (“Rafe”) Vaughan Williams never got over it either. One must expect that of dangerous literature. Like Cabell’s Music from Behind the Moon [4], it fills one with a strange longing that can never be satisfied until the world, and oneself, is forever changed. As Cabell wrote of altogether different music,

It was a strange and troubling music she made there in the twilight, and after that the slender mist-like woman had ended her music-making, and had vanished as a white wave falters and is gone, then Madoc could not recall the theme or even one cadence of her music-making, nor could he put the skirling of it out of his mind. Moreover, there was upon him a loneliness and a hungering for what he could not name.

Whitman hit me like that, when I was a kid too young to defend myself. Well, if the theme of this concert is “beauty and loss”, we’re pretty much on target here.

It’s hard to appreciate Whitman enough nowadays, with the ideals of democracy and free-thinking built into American society right down to the keel-blocks (with notable exceptions of late for Republicans repenting of democracy, e.g., Washington Republican officials saying “We do not want to be a democracy.” [5]). For late Victorians, that hit like a bombshell.

Whitman, for me, is all about facing death (“… to die is different from what any one supposes, and luckier”, as he put it elsewhere in Leaves of Grass). “Toward(s!) the Unknown Region” is about being brave enough to step confidently into the dark. As an old man who thinks more about personal death than I used to, the ending still brings tears to my eyes:

Till, when the ties loosen,

All but the ties eternal, Time and Space,

Nor darkness, gravitation, sense, nor any bounds bounding us.Then we burst forth, we float,

In Time and Space O soul, prepared for them,

Equal, equipt at last, (O joy! O fruit of all!) them to fulfill, O soul.

I may not have strong faith, but I have hope. Perhaps we can “fulfill” nature; maybe one day I’ll even understand what that means. Whitman was, as far as I can tell, crazy as a loon – but it was the Divine Madness.

Ives: Psalm 90 (1924)

Ok, Charles Ives next. Again, this is a composer whose music does not move me, but his source material is excellent, in the choice of Psalm 90. Generally, I love the Psalms, especially the central Davidic ones that start with despair and end with hope.

Ehrlich says in his program notes that this piece may be the only one with which Ives was ever fully satisfied:

… Charles Ives’s truly cosmic setting of Psalm 90, with it extraordinarily exposition of music and text oscillating between conflict and resolution…

A cosmic view is appropriate here, since the source text is… well, cosmic. The first 2/3 is (almost) despairing at the cruelty of the world and our short lifespans within it. Ives is appropriately dissonant, conflicted, and difficult. I spent some time watching the musicians on the tubular bells, and seeing the gates of the great organ open and close when the music was too overwhelming to bear.

But then at the end comes a prayer and its musical resolution:

O satisfy us early with thy mercy; that we may rejoice and be glad all our days.

Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.

Let thy work appear unto thy servants, and thy glory unto their children.

And let the beauty of the Lord our God be upon us: and establish thou the work of our hands upon us; yea, the work of our hand establish thou it. Amen.

Indeed, transcendence and immanence: the world can be better, let us help each other to do better.

Vaughan Williams: Serenade to Music (1938)

Where Ehrlich’s program notes mention “beauty and loss” as a theme for the night, some of it is apparently quite personal:

… I knew long ago that I wanted Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Serenade to Music to be my final farewell, as it seemed to philosophically and musically contain, with hits superbly appropriate text from Shakespeare, much of what has been important to my love of music and subsequent music-making. Not coincidentally,l this work was first brought to my attention by a childhood friend, who only last month I learned had unexpectedly passed away. I will have his memory in mind as this music flows forth tonight.

And of course, more Vaughan Williams was a welcome balm after the dissonance.

The text is from Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene 1. It is difficult to appreciate what would later be called the “music of the spheres” that has a divine nature, while we are mortal beings:

Such harmony is in immortal souls;

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.

Yes, it’s hard to perceive the divine:

I am never merry when I hear sweet music.

The reason is, your spirits are attentive:

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not mov’d with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are as dull as night, And his affections are as dark as Erebus;Let no such man be trusted.

That’s very much in line with a sentiment of Sappho we’ve quoted before on this CLBTNR. When Senator Tuberville of Alabama criticized the crew of a US Navy ship for having a poetry night, Sappho #65, “To One Who Loved Not Poetry,” was just about the only thing to say to barbarians who reject poetry:

κατθάνοισα δὲ κείσῃ οὐδέ ποτα

μναμοσύνα σέθεν

ἔσσετ’ οὐδὲ †ποκ’†ὔστερον· οὐ

γὰρ πεδέχῃς βρόδων

τῶν ἐκ Πιερίας· ἀλλ’ ἀφάνης

κἠν Ἀίδα δόμῳ

φοιτάσεις πεδ’ ἀμαύρων νεκύων

ἐκπεποταμένα[8]But thou shalt ever lie dead,

nor shall there be any remembrance of thee then or thereafter,

for thou hast not of the roses of Pieria;

but thou shalt wander obscure even in the house of Hades,

flitting among the shadowy dead.

Always a useful way to slap down a barbarian (such as myself?!), which is what Shakespeare does in the first part. That corresponds to the “complaint” part of a Davidic Psalm, followed by the more exalted response to ordinary music (“music of the house”):

Music! Hark!

It is your music of the house.

Methinks it sounds much sweeter than by day.

Silence bestows that virtue upon it.

…

Soft stillness and the night

Become the touches of sweet harmony.

And so to bed: with that, John Ehrlich steps down as music director of the Spectrum Singers.

The Weekend Conclusion

This was well done: even using some composers with whom I am not terribly compatible, the

Spectrum Singers (and their all-important pre-concert lecture and program notes) made me

thoughtful about spiritual meaning in a difficult world, and what role death will

eventually play for me.

This was well done: even using some composers with whom I am not terribly compatible, the

Spectrum Singers (and their all-important pre-concert lecture and program notes) made me

thoughtful about spiritual meaning in a difficult world, and what role death will

eventually play for me.

A choir that does that, of course, inevitably brings us to George Eliot’s poem “The Choir Invisible” [6], with its use of a choral metaphor as transcendence of a mortal world, into Whitman’s “different and luckier” realm:

Poor anxious penitence, is quick dissolv’d;

Its discords, quench’d by meeting harmonies,

Die in the large and charitable air.

…

This is life to come,

Which martyr’d men have made more glorious

For us who strive to follow. May I reach

That purest heaven, be to other souls

The cup of strength in some great agony,

Enkindle generous ardor, feed pure love,

Beget the smiles that have no cruelty,

Be the sweet presence of a good diffus’d,

And in diffusion ever more intense!

So shall I join the choir invisible

Whose music is the gladness of the world.

The world is difficult. May our “poor anxious penitence” be in the “large and charitable air”, even in a difficult world.

(Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.)

Notes & References

1: E Symkus, “One more show for Spectrum Singers conductor John Ehrlich before he takes his final bow”, Boston Globe, 2024-May-13. ↩

2: Vi Hart, “Twelve Tones”, YouTube, 2014. ↩

3: CS Lewis, “The Great Divorce”, MacMillan, 1946. ↩

4: JB Cabell, “Music from Behind the Moon: An Epitome”, John Day, 1926. ↩

5: D Westneat, “The WA GOP put it in writing that they’re not into democracy”, Seattle Times, 2024-Apr-24. ↩

6: George Eliot, “The Choir Invisible”, collected in The Poems of George Eliot, 1867.

Mary Ann Evans wrote pseudonymously as George Eliot, due to the sexism of her day. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.