We need the Talmudic argument style… someday

Tagged:Politics

/

Religion

/

SomebodyAskedMe

/

TheDivineMadness

Somebody asked me about the style of argument used when discussing the Talmud, a centuries-long rabbinical dialog on Jewish Law. The style involves not so much winning (though there is that), but mostly about understanding multiple points of view. Sound like something the world could use about now?

It’s an unusual question, since neither my friend nor I are Jews. I am, though, religious with as much affection for Judaism as an outsider can reasonably have… so maybe not completely unusual.

On having deeper conversations

My friend was reacting to a New York Times piece by

David Brooks [1]

on having “deeper conversations”, particularly this bit:

My friend was reacting to a New York Times piece by

David Brooks [1]

on having “deeper conversations”, particularly this bit:

Find the disagreement under the disagreement. In the Talmudic tradition when two people disagree about something, it’s because there is some deeper philosophical or moral disagreement undergirding it. Conversation then becomes a shared process of trying to dig down to the underlying disagreement and then the underlying disagreement below that. There is no end. Conflict creates cooperative effort. As neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett writes [2], “Being curious about your friend’s experience is more important than being right.”

Now, normally I don’t have time for guys like Brooks. I am made ill by the delusions of conservative pundits. I am enraged by the ones that call themselves “centrists”, with their banal evil and false neutrality of both-siderism [3] to avoid naming and shaming the right-wing shenanigans.

But this time… I gotta admit, this is a bit of all right. My friend described his reaction thusly:

I found this paragraph fascinating in ways I am still carefully unwrapping, as I would delicately unfold tissue paper holding an object of great value that belongs to history and not to me…

How might it have come to pass that Jews have learned the art of learned argument from a viewpoint of mutual respect, and how might their example teach the rest of us?

Architecture of a Talmud page

The Talmud appears, to this non-Jew, to be something of an artifact engineered to do

exactly this. Unlike the Torah, with its magisterial pronouncements, the Talmud is a

series of arguments in conversation with each other over the centuries – mixed

with no small amount of stories and jokes. An excellent BBC News article by William

Kremer [4] illustrates this with the anatomy of a typical page:

The Talmud appears, to this non-Jew, to be something of an artifact engineered to do

exactly this. Unlike the Torah, with its magisterial pronouncements, the Talmud is a

series of arguments in conversation with each other over the centuries – mixed

with no small amount of stories and jokes. An excellent BBC News article by William

Kremer [4] illustrates this with the anatomy of a typical page:

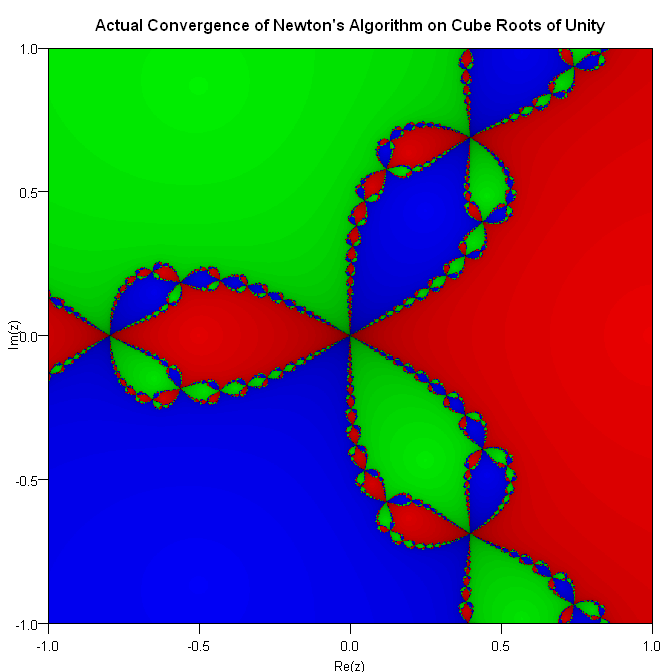

- First, of course, is the law: the Torah, or Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament as Christians like to call it. This is preserved in several forms, whether via the Septuagint, or the Masoretic text, or other sources.

- The Talmud is an attempt to preserve the oral tradition (what the Law means in terms of daily living) during the Roman occupation of Judea, starting around the second century with Judah ha-Nasi and successors. This is roughly the Mishnah, in the center of the page (colored pink in the illustration).

- The next part is the Gemara, indicated in yellow in the illustration just below the Mishnah. It’s a series of discussions, amplifications, and arguments about the Mishnah, the Torah, and other sources. It has thesis statements, questions, responses, discussions, … which rarely finally settle anything.

- Next, in blue in the illustration wrapped around the Mishnah & Gemara to the upper right, is the commentary of Rashi, an 11th century French rabbi. It’s rendered in a special font (Rashi text). You know you’re beginning to be A Bit of a Big Deal when you get your own commentary area on each page of the Talmud, and people invent a font just for you.

- Finally, wrapped around everything else on the left, bottom, and right is commentary and glosses from everybody else (show green in the illustration). These are mostly 10th century rabbis, but there can also be modern interpretations especially about language. There are a lot of cross-references to other passages with similar topics or similar language, or where legal rulings in medieval Jewish law are relevant.

Kremer consults Gila Fine, editor-in-chief of Maggid Books in Jerusalem on her experience as a woman studying Talmud (usually restricted to men among the more Orthodox):

Unlike the lofty, magisterial prose of the Torah, she found the Talmud to have “all the imperfections, the trivialities, the multiplicity of voices, the wild associations - everything that characterises human conversation.”

But Fine eventually fell in love with the book and is now overseeing the publication of a new edition. She relates in particular to the Aggadah, the folkloric stories in the Talmud, which rub shoulders with the dense, legalistic Halakha text, and seem sometimes to subvert it.

“You have stories of women who criticise men, of non-Jews who put Jews to shame, of poor simple folk who make a mockery out of rabbis - there’s something very liberated and liberating about Aggadah,” she says.

On arguments to sharpen our (mutual) understanding

So the Talmud encourges argument because it is an argument in some ways: the very page layout tells you this. It is conducted over millennia, via commentaries written by the deepest scholars of the Law, with lots of stories and jokes along the way… and you’re invited to join. Because it’s a little more speculative, sometimes crazy, it invites discussion in a way that the majesty of the Torah does not.

It’s a respectful argument because the goal is not to dominate all the other viewpoints, but to understand all the other viewpoints in their full complexity and multiplicity. None of the predecessor commentaries came to universal agreement, so why should you? Your partner is not wrong; you’re just trying to add another aspect to your mutual understanding. The world is, after all, not simple, so neither is our spiritual understanding of it.

(With all the cross-references, one might argue that it is an example of early attempts at hypertext. I’ve also heard this claim made about Thomas à Kempis’s 15th century book, De Imitatione Christi [5]: each chapter is 1 page on 1 topic, with cross-references to many other chapters. In fact, my introduction to De Imitatione Christi was via Hypercard in the late 80s.)

On humor

Ok, if we’re going to mention the folklore and jokes in the Talmud, we have to talk about

Scott Alexander’s novel, Unsong. [6] It takes ideas from

the Talmud and asks, “What if the world was literally like that?”

Ok, if we’re going to mention the folklore and jokes in the Talmud, we have to talk about

Scott Alexander’s novel, Unsong. [6] It takes ideas from

the Talmud and asks, “What if the world was literally like that?”

As a science fiction novel, it’s brilliant:

- Uriel, the nerd sysadmin angel, trying to keep reality running

- Silicon Valley full of “big theonomy” companies trying to copyright the Names of G-d from kaballah used for spells

- Unitarian Universalist underground cells doing samizdat kaballah

- a battle in which the Lubavitcher Rebbe turns the Statue of Liberty into a golem and rides it into battle saving the day

- loads of puns involving Torah stories and whales (example: “Baleen Shem Tov”)

- trying to explain knock-knock jokes to an angel

- why Elisha Ben Abuyah is always referred to as “the other one” in the Talumd

… and a lot of even crazier stuff. (Uriel says: “PLEASE DO NOT BLOW UP MOUNTAINS. IT NEVER HELPS.”)

Scott’s a psychiatrist, and said the free associations used in kaballah are very like the free associations some of his stranger patients had. Their world views not only made sense to them, they made perfect sense. More sense than reality should make.

Trust me: if you’re interested in Jewish thinking, it’s utterly hilarious. Even if you’e not, it’s still pretty funny.

What does that say about American politics?

Of course, to have a properly respectful dialog as in the Talmudic tradition, it takes both sides being committed to that attitude. You can’t have Talmudic dialog with a fanatic who denies your right to exist, or the fundamental legitimacy of your ideas. That would be like the Israelis attempting Talmudic dialog with Hezbollah, for example: respectful dialog is the wrong response to someone who denies your right to exist. I see nothing but venom, rage, and contempt coming from the American Republican right at the moment; respectful dialog is not even remotely the correct response to Trump.

This is why I’m so frustrated with the mindless both-siderism of people like Brooks: his article makes an excellent point, but one which is of no applicability when attempting to talk to Republicans. The time for respectful dialog will come, when there is mutual respect. Though probably not with this version of the Republican party.

We should all live so long. (No, really: we should.)

Notes & References

1: D Brooks, “Nine Nonobvious Ways to Have Deeper Conversations: The art of making connection even in a time of dislocation”, New York Times, 2020-Nov-19. ↩

2: L Barrett, “How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain”, lisafeldmanbarrett.com, retrieved 2020-Nov-29. ↩

3: E Ward, “The Banality of Evil: The Mainstreaming of Both-Siderism”, Western States Center at Medium.com, 2020-Aug-28. ↩

4: W Kremer, “The Talmud: Why has a Jewish law book become so popular?”, BBC News, 2013-Nov-08. ↩

5: Thomas à Kempis, De Imitatione Christi, 1418-1427. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Great article, Weekend Editor. I like the colored graphic of the page from the Talmud. It helps me visualize things better. And of course, I’ve always enjoyed your humor!