On the Efficacy of COVID-19 Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

Tagged:COVID

/

JournalClub

/

MathInTheNews

/

Politics

/

R

/

Statistics

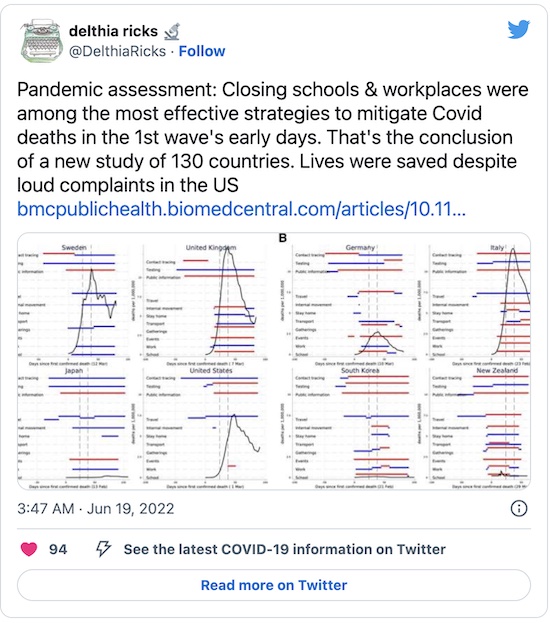

Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) have been controversial: people continue to object loudly and strongly to things like masking, social distancing, and closures of schools and workplaces. We now have some retrospective data: how have each of those measures performed, in terms of live saved for the complaints they’ve caused?

A study of COVID-19 NPIs in 130 countries

From Delthia Ricks comes a heads-up to a study on NPI’s vs COVID-19 world-wide:

She’s referring to a worldwide study of NPI effectiveness during the pandemic by

researchers mostly based at the University of Manchester (England), published a couple

weeks ago in BMC Public Health. [1]

She’s referring to a worldwide study of NPI effectiveness during the pandemic by

researchers mostly based at the University of Manchester (England), published a couple

weeks ago in BMC Public Health. [1]

The authors are careful to point out (in the first sentence of the abstract, no less!) that while NPIs are empirically known to work, they:

- Can have negative effects on mental health (as we are all painfully aware) and on economies (as the current supply chain madness demonstrates), and

- Can be a result of voluntary action by people ahead of a mandate. For example, in Japan wearing of face masks to prevent disease transmission (even as simple as a cold) is customary. Since everybody masked up immediately, a mask mandate would have no effect. Conservatives would point to that and say “See? Masks don’t work!” when exactly the opposite is true.

They studied the first wave of COVID-19 “to limit reverse causality”, i.e., people looking back at what worked in the first wave to decide what to do in the subsequent waves. So we’re looking at 0 - 24 days and 14 - 38 days after the first COVID-19 death in each country. This properly accounts for the lag in deaths from onset of infection, which is the only thing policies can affect. (It does not appear they corrected for the fact that countries with later waves could look at those with earlier waves to see what worked and what did not?)

They studied 9 NPIs in 130 countries tracked by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT):

- school closing

- workplace closing

- cancelled public events

- restrictions on gatherings

- closing public transport

- stay at home requirements (‘lockdown’)

- restrictions on internal movement

- international travel controls

- public information campaigns

While they display the usual reluctance to show any math common to biology/medical/public health folk, there are a few clues we can glean (mostly from the Supplement). It looks like they mostly did a set of linear regressions of per capita deaths over time separately by country, on the various policy variables and confounders.

- Univariate linear regressions of per-capita death rates on policies were apparently used for

feature selection, though they didn’t

quite use that word.

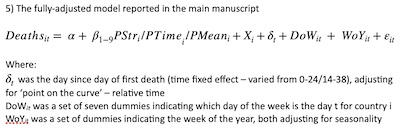

- Then they started combining policies together, along with a variety of confounders including day of week and week of year to account for weekend dropouts and seasonality. That’s the model reported in the main manuscript, as shown here from the Supplement.

- They also did some nonlinear modeling using a generalized linear model (GLM) with apparently a negbinomial link function, to model counts. However, this does not appear to have made it into the main manuscript, nor does it appear to have influenced their conclusions. I’m not sure why it was included!

As is always the case when authors exile math to the Supplement, it was written with an uncritical hand and they kind of made a hash of it. I sort of grasp what they did, but not enough to check. Very frustrating!

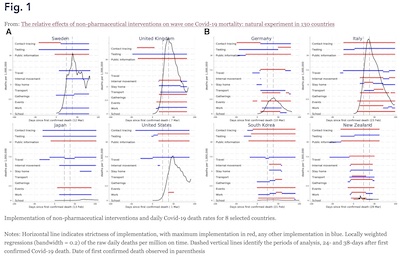

Figure 1, reproduced here, shows the empirical association between the daily per capita

death rates and various policies.

Figure 1, reproduced here, shows the empirical association between the daily per capita

death rates and various policies.

- Each plot calls out a particular country; the US is the 2nd plot from the left in the bottom row.

- The horizontal axis is time, starting at 0 from the first COVID-19 death. The study periods are from 0 to 24 days and to 14 38 days, with ending periods shown by the vertical dashed lines.

- The vertical axis is the per capita daily death rate, in deaths per million. The data has been smoothed with a locally weighted regression with bandwidth 0.2. I think that means something vaguely like a convolution with a Gaussian (possibly causal) or a local linear regression in a sliding window with some sort of weighting… but of course they don’t disclose enough detail to tell!

- The colored red and blue lines indicate when various policies kick in. Red is the most stringent level, and one or two levels below that are indicated in blue.

We see clearly the awful shape of the first wave’s death rates. But we also see that this is a pretty gnarly multivariate statistical problem. We’d best use more careful models than simply eyeballing the data! As the authors say:

Notably, elucidating mortality impacts from separate interventions using visual aids, or statistically without controlling for those co-introduced, is problematic given the introduction of multiple interventions.

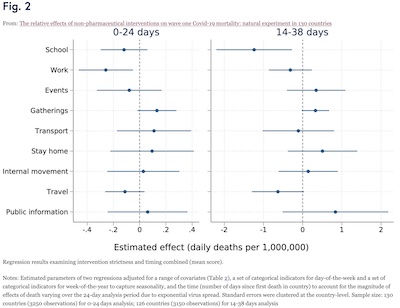

Figure 2, reproduced here, shows the result of that more nuanced analysis. It’s a pooled

cross-sectional regression (regress in each country, and combine the results) of the

effects of all 9 interventions, both based on strictness and timing. Stricter and earlier

interventions worked better, saving more lives.

Figure 2, reproduced here, shows the result of that more nuanced analysis. It’s a pooled

cross-sectional regression (regress in each country, and combine the results) of the

effects of all 9 interventions, both based on strictness and timing. Stricter and earlier

interventions worked better, saving more lives.

- Here the horizontal axis is the regression coefficient, with the mean shown with a dot and the 95% confidence limits indicated by the whisker.

- An intervention is effective if the coefficient is negative.

- An intervention is statistically significant at the $p \lt 0.05$ level if the confidence interval whisker is bounded below 0.

The results seem to be:

- School closures were effective and statistically significant in the 14-38 day period, and effective but not quite statistically significant in the 0-14 day period.

- Workplace closures were effective and statistically significant in the 0-14 day period, and effective but not quite statistically significant in the 14-38 day period.

- Travel restrictions were effective in both periods, but just barely not statistically significant.

- No other intervention was statistically significant, and indeed all of them were sometimes ineffective, i.e., increasing per capita death rates in at least one period.

(NB: Mask usage, my favorite NPI, was not tested and cannot be analyzed from these data.)

Note that the interventions that mattered were both publicly measurable, and hence could be made mandatory and enforced. The more voluntary, at-home interventions were not publicly measurable, and thus enforcement more spotty. As the authors said:

However, it may be unexpected that workplace and, particularly, school closures were associated with relatively lower Covid-19 mortality across countries whilst interventions such as stay-at-home measures were not. One plausible interpretation is that schools and workplaces involve ‘compulsory’ interactions with others, as individuals feel obliged to attend in person and may be concerned for loss of earning or educational opportunities. This compares to interventions targeting other sources of human interaction which are more ‘voluntary’ and may reduce irrespective of whether mandated policies are introduced (therefore giving no additional observable effect of introducing the intervention).

The school closure efficacy is interesting. Kids may not be personally affected so much by COVID-19, but they can be asymptomatic carriers who infect their elders, and thus bump up the death rate. Low personal risk is not low public risk!

The Weekend Conclusion

The findings are clear:

- School closures were effective (-1.23 daily deaths per million, 95% CL -2.20 to -0.27).

- Workplace closures were effective (-0.26 daily deaths per million, 95% CL -0.46 to -0.05).

- Both of those were mandatory; by comparison voluntary measures were not effective.

- These findings were robust across multiple statistical techniques, e.g., both ordinary least squares regression and negbinomial regression.

- Masks were not tested, so we can draw no conclusions from these data. However, based on other data, I believe they would have been found highly effective.

Of course, the most effective preventive measure is vaccination, so that’s the first avenue to pursue.

The most effective NPIs are the measures about which people, particularly conservatives, whine incessantly. But they save lives! Do you value your ideology more than you value the lives of your neighbors?! The evidence says that American Republicans do indeed cling to their ideology with a sociopathic degree of self-regard. But their policies are factually incorrect, and their embrace of those policies is morally incorrect.

Notes & References

1: J Stokes, et al., “The relative effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on wave one Covid-19 mortality: natural experiment in 130 countries”, BMC Public Health 22:1113, 2022-Jun-03. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-022-13546-6. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.