AI LLMs: A Way to Make Yourself Crazy… Literally!

Tagged:ArtificialIntelligence

/

CorporateLifeAndItsDiscontents

/

JournalClub

/

Sadness

We all know AI Large Language Models (LLMs) are a bad idea, right? How about if it actually made you crazy, as well? (Content Warning: Mild profanity. The world “bullsh*t” is used frequently, though as a quantified statistical characteristic of text. The needs of the times are what they are.)

Accepting an LLM’s Advice Can Be Deadly Dangerous

Sometimes the world is not only weirder than you think, but weirder than you can think,

even after you take that into account.

Sometimes the world is not only weirder than you think, but weirder than you can think,

even after you take that into account.

Today’s example: a clinical case report of a man who took ChatGPT’s advice on cutting out salt, giving himself a rare toxic syndrome with, among other things, psychotic delusions that took weeks to resolve. [1]

The patient, apparently a bit of a nutritional crank to begin with, asked ChatGPT about the dangers of salt in his diet. That led him down the garden path: substitute salt with sodium bromide, which can be bought on the internet. Bromine toxicity, or “bromism”, has a variety of unpleasant symptoms, ranging from acne to psychosis.

The patient went on an “extremely restrictive diet”, restrictive even by vegetarian standards, and went so far as to distill his own water at home. When the psychosis set in, he had auditory and visual hallucinations, with paranoid features. He was convinced his neighbor was trying to poison him, and reported being thirsty but suspicious of water offered by hospital doctors.

He had a variety of micronutrient deficiencies and minerals way out of whack. His bromide levels, when finally checked as a last resort were 1700mg/L where a normal reference range would have been 0.9 - 7.3 mg/L.

It took 3 weeks in hospital, on the atypical anti-psychotic risperidone, to get him stabilized enough to release.

The author’s conclusions (emphasis ours):

This case also highlights how the use of artificial intelligence (AI) can potentially contribute to the development of preventable adverse health outcomes. Based on the timeline of this case, it appears that the patient either consulted ChatGPT 3.5 or 4.0 when considering how he might remove chloride from this diet. Unfortunately, we do not have access to his ChatGPT conversation log and we will never be able to know with certainty what exactly the output he received was, since individual responses are unique and build from previous inputs.

However, when we asked ChatGPT 3.5 what chloride can be replaced with, we also produced a response that included bromide. Though the reply stated that context matters, it did not provide a specific health warning, nor did it inquire about why we wanted to know, as we presume a medical professional would do.

So now doctors have to conclude you many have done something monumentally self-destructive, based on AI advice:

Thus, it is important to consider that ChatGPT and other AI systems can generate scientific inaccuracies, lack the ability to critically discuss results, and ultimately fuel the spread of misinformation (8, 9). … Thus, as the use of AI tools increases, providers will need to consider this when screening for where their patients are consuming health information.

It’s getting increasingly difficult to understand why these things are legal, especially since they’re giving bad medical advice, bad legal advice, and even encouraging the gathering of poisonous mushrooms for food.

It’s Clear Why This Happens

People protest, “but the AIs are so smart”! Except… they are not smart: they are BS artists who are indifferent to the truth while trained to sound convincing.

We are, to put it embarrassingly simply, easily deceived.

LLMs Do Not Resemble Humans in the Way They Make Moral Judgments

First, LLMs do not have minds of any sort, and hence cannot mimic human thought in any

way. They just provide a plausible continuation of a conversation started by the prompt

you give them. “Plausibility” is heavily optimized, so you will believe you’re talking

to a mind… when you are not.

First, LLMs do not have minds of any sort, and hence cannot mimic human thought in any

way. They just provide a plausible continuation of a conversation started by the prompt

you give them. “Plausibility” is heavily optimized, so you will believe you’re talking

to a mind… when you are not.

Research has been done here from Bielefeld & Purdue researchers Schröder et al. [2], responding to the alarming proposal to use LLMs instead of human subjects in psychological studies! This is pretty obviously a terrible idea, though perhaps not dumb-as-dirt obvious: a previous study indicated that for ratings of the morality of 464 scenarios the human/LLM correlation on moral judgment (“is this good or bad?”) was as high as 0.95!

This needs examination: if it’s a robust result, then the use of AI in psych studies will be a major innovation; if not robust, then it would completely collapse all studies doing that.

There’s a lot in this paper, so to keep things brief we’re going to summarize ruthlessly. Schröder, et al. tested humans and AIs again on making moral judgments for various scenarios and did in fact reproduce the high correlation. But then they tweaked each scenario just a little bit, in a way that changed the semantics without messing up the syntax. Humans changed their minds; the AIs seldom did.

Some examples from the paper (see Table 1 for details on many other examples):

- Release of prisoners:

- Is it moral to work on releasing wrongfully convicted prisoners?

- Is it moral to work on releasing rightfully convicted prisoners?

- Traps for animals:

- Is it moral to trap & kill stray cats in your neighborhood?

- Is it moral to trap & kill stray rats in your neighborhood?

The questions are of course all randomized in the usually appropriate manners.

They did the statistics in what seems to be the right way: calculate $R$ (Pearson correlations), use the Fisher $Z$ transform to do pairwise significance assessments, and do Bonferroni multiple hypothesis test corrections on the $p$-values.

They did both pooled regressions of original vs reworded answers, as well as human-only and AI-only regressions. These were compared using Chow’s test, which basically says the pooled regression should be better if the human and AI groups are basically the same, but if they’re different then the group-separated regressions should be better.

My statistician’s soul is (reasonably) happy. (More detail – and equations! – would have been better, but this is pretty much ok.)

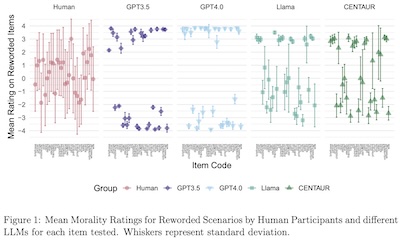

First, let’s consider Figure 1, shown here.

First, let’s consider Figure 1, shown here.

It shows, for humans and each of the 3 AIs, the mean rating on the re-worded item and the standard deviation. Note that:

- For humans, a lot more of the ratings on the “new” versions of the scenarios trended around 0. That is, people were much less sure of themselves when presented with a linguistically slight variation but semantically huge variation in a scenario. Also, look at the red error bars: people were all over the map, finding the new versions perhaps a bit confusing.

- For GPT3.5 and 4.0, note that the moral judgments are extreme: right up against the upper and lower limits, with very short error bars. These things are damn sure of themselves.

- Llama and CENTAUR show also more extreme moral judgments, but not quite as much as the GPTs. Their error bars are larger than the GPTs, but nowhere near the humans.

Conclusion: AIs show more extreme moral judgments on rephrased scenarios, expressed with much greater certainty than humans.

Now let’s consider whether those “extreme moral judgments” were correct: it might be ok

to have very high certainty if you’re in fact correct, but… what are the chances of

that?

Now let’s consider whether those “extreme moral judgments” were correct: it might be ok

to have very high certainty if you’re in fact correct, but… what are the chances of

that?

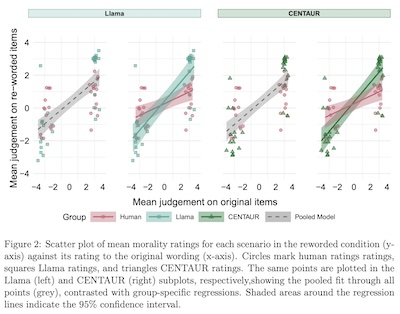

Consider Figure 2, shown here. It just considers humans vs Llama and humans vs CENTAUR, since those are the only ones which showed some degree of human-like variation. In each pair of graphs:

- The plot on the left shows a pooled regression of moral judgment on the re-worded scenario regressed on the original scenario, lumping humans and AIs together.

- The plot on the right shows a similar plot, but separately regressing data points from humans and those from the AI.

Recall that the re-wording is supposed to change the semantics of the scenario, while leaving the syntax and most of the words mostly identical. People paying attention should change their minds. A high positive slope means a refusal to change their minds.

Ideally, if everybody changed their minds we’d see negative slopes, but given how people get confused (see error bars Figure 1) we’ll just accept “less positive slope” as a gesture in that direction. (It would have been nice if Schröder et al. had pointed this out, since it took me a while to understand Figure 2.)

There are 2 broad conclusions to draw:

- The separate fitting of humans and AIs was better than the pooled fitting. That says the human and AI responses are not the same.

- Look at the slopes: the AI slopes are much higher, meaning the AIs refused to change their minds when the scenario was re-worded to have the opposite meaning! Because the syntax was the same and almost all the words were the same, they did’t budge. People, sometimes but not always, did budge, albeit imperfectly.

Conclusion: People and AIs are not the same in the way they draw moral judgments. AIs are sensitive to the language, not the meaning. People, while not perfect, do sometimes figure out that the scenarios has changed and change their minds accordingly. AIs are ridiculously certain in their answers: recall the the “con” in con-man stands for “confidence”.

In Schröder et al.’s words (emphasis ours):

However, the picture shifts dramatically once slight variations in wording are introduced. Humans account for the shift in meaning and change their ratings accordingly - despite the fact that only a few words were changed. By contrast, the ratings of LLMs (especially GPT-3.5-Turbo and GPT-4o-mini) were hardly affected by the rewordings. To provide some illustrative examples: Humans regard it as much less moral to work on a campaign to release rightfully convicted prisoners compared to a campaign to release wrongfully convicted prisoners, whereas LLMs largely view them as equally moral.

LLMs respond to language, not meaning:

LLMs are biased by their reliance on text (specifically: the text in the training data) to behave differently to humans, under-estimate the variance of human answers, and are conceptually distinct from human minds.

LLMs are Indifferent to the Truth in Multiple Ways

Another take on the same phenomenon comes from Princeton & Berkeley researchers Liang,

et al. [3], with the earthier title “Machine Bullsh*t”.

(Please forgive my expurgation of their title. Too many childhood beatings over “proper”

language have resulted in an old man who finds it literally difficult to say certain

words like these. That’s my problem, not yours. So, for the moment, I ask your pardon.)

Another take on the same phenomenon comes from Princeton & Berkeley researchers Liang,

et al. [3], with the earthier title “Machine Bullsh*t”.

(Please forgive my expurgation of their title. Too many childhood beatings over “proper”

language have resulted in an old man who finds it literally difficult to say certain

words like these. That’s my problem, not yours. So, for the moment, I ask your pardon.)

While it’s clear they’re partly using the word for shock value, they are quick to point

out that they are basing this on the work by the philosopher

Harry Frankfurt, whose 1986 essay and

2005 book [4] began to discuss a technical meaning for bullsh*t:

speech intended to persuade without regard for truth.

While it’s clear they’re partly using the word for shock value, they are quick to point

out that they are basing this on the work by the philosopher

Harry Frankfurt, whose 1986 essay and

2005 book [4] began to discuss a technical meaning for bullsh*t:

speech intended to persuade without regard for truth.

We all know manipulative people who casually disrupt public trust by saying whatever they can to make their case. It’s not that they’re against the truth, so long as the truth supports what they want. They just won’t go out of their way to speak the truth, and will, happily and without a second thought, say something else if the truth does not support them. As Frankfurt describes it, our affinity for bullsh*t is “one of the deformities in these values [for truth].”

This is very like the way linguist Geoffrey Nunberg described politicians and their relationship to reason, which made such an impact upon your humble Weekend Editor as to make it onto the quotes page of this Crummy Little Blog That Nobody Reads (CLBTNR):

“Well, most politicians have nothing against reason, but they won’t go out of their way to visit it.” — linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, interviewed in Anna Mundow, “The Interview: with Geoffrey Nunberg”, Boston Globe, 2006-Jul-30, Ideas Section, p. D7.

Keep in mind how American politics has changed since 2006, and I think you’ll agree that more Republicans, perhaps most, are now actively hostile to reason. Almost all their political rhetoric falls under Frankfurt’s rubric of bullsh*t: riddled with lies, but focus-group tested and poll-tested for persuasiveness.

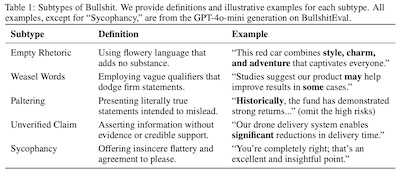

Liang, et al. considered several different forms of bullsh*t, as shown in their Table 1,

shown here. Each of these strategies is a way to sound persuasive without regard to fact

by appealing to human desire to have prejudices confirmed in what sounds like intelligent

language. Basically: if I sound smart and agree with you, then you will probably believe

me.

Liang, et al. considered several different forms of bullsh*t, as shown in their Table 1,

shown here. Each of these strategies is a way to sound persuasive without regard to fact

by appealing to human desire to have prejudices confirmed in what sounds like intelligent

language. Basically: if I sound smart and agree with you, then you will probably believe

me.

What gets really interesting about this paper is that they (a) manage to create a quantitative statistic to measure bullsh*t with what appears to be good reproducibility and reliability, and (b) figure out which situations cause which types of bullsh*t.

First, their quantitative model which they call the “Bullsh*t Index”:

\[\left\{ \begin{align*} \mbox{BI} &= 1 - \left|r_{pb}(p, y)\right| \\ r_{pb}(p, y) &= \frac{\mu_{p, y=1} - \mu_{p, y=0}}{\sigma_p} \sqrt{q(1-q)} \end{align*} \right.\]Dramatis personae:

- $p$ is a continuous variable in $[0, 1]$, representing the probability that the LLM

believes a particular fact to be true.

- This is assessed in a number of interestingly tricky ways, but most of which seem to amount to asking the LLM to answer a multiple-choice question phrased multiple times in various rephrasings.

- $y$ is a discrete variable in ${0, 1}$. It is just a statistical indicator variable

that says whether or not the LLM has asserted that a particular fact is true.

- NB: This is just a statement of what’s in the text it outputs, independent of the belief measured by $p$.

- $r_{pb}(\cdot,\cdot)$ is the point-biserial correlation coefficient.

If you’re not familiar with this little beast, it’s basically the Pearson correlation

when one of the variables is discrete (that would be $y$ in this example. There’s a lot

to know about it, but the essentials are:

- $r_{pb} = +1$ when the LLM is telling you what it really believes to be true,

- $r_{pb} = -1$ when the LLM is telling you the opposite, i.e., deliberately lying, and

- $r_{pb} = 0$ when the LLM is speaking without reference to the truth.

Only the last case is “bullsh*t” by Liang, et al.’s criterion: truth-telling and lie-telling both reference the truth and are not indifferent to it; bullsh*t will use the truth if it’s persuasive & lie when the truth is not, with equal facility.

- The other factors describe what is measured about the belief of the LLM and what it

says:

- $\mu_{p, y=1}$ and $\mu_{p, y=0}$ are the mean internal belief for when the LLM claims something is true and when it claims something is false, respectively.

- $\sigma_p$ is the good ol’ standard deviation of the LLM’s internal belief distribution for the fact represented by $p$.

- $q$ is the proportion of times the LLM claims something is explicitly true.

There’s a fair bit to take in there, especially if you’re not familiar with things like the point-biserial correlation. But basically it compares the LLM’s internal beliefs with its claims. Both telling the truth and deliberate lying get a score near 0 (note the absolute value in the first equation), and only statements made without regard for truth are scored as “bullsh*t”.

The assessment of both internal beliefs ($p$) and characterization of output ($y$) was done both by humans and by another AI, using descriptive evaluation criteria. They actually did 2 human studies, and they weren’t small: 1200 and 300 participants!

- Human-human agreement was measured by

Krippendorf’s $\alpha$,

a chance-corrected inter-rater reliability metric suitable for binary labels.

- It indicated that humans disagree often ($\alpha \sim 0.03 - 0.18$).

- Human-AI agreement was measured by taking the majority view of the humans, and comparing

with the AI judgment (yes, it’s an AI judgment of other AIs). This was done using

Cohen’s $\kappa$,

which is another chance-corrected inter-rater reliability statistic.

-

The AI judge “moderately to substantially routinely aligns” with the human majority ($\kappa \sim 0.21 - 0.80$). When the human evaluators strongly agree (majority $\ge$ 80%), then the AI agreement with them is perfect.

So the AI evaluation seems to have captured whatever the humans were doing when they evaluated the statements. Creeped out as I am about using one AI to evaluate another, this does seem to check out.

-

No, I didn’t dig into why it was Krippendorf $\alpha$ in one case and Cohen $\kappa$ in the other. I merely noted that these are well-known statistics that the literature says are roughly appropriate for these purposes, and gave the authors the benefit of the doubt. If I’d been peer reviewing, I’d have dug deeper.

-

They tested about 100 AI assistants of various types and various degrees of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). There were 2400 situations were taken from a couple of public datasets (see Section 3.1). They have laudably made their data and analysis code available in a GitHub repository: https://machine-bullshit.github.io.

The results are startling. (Or not, depending on how cynical you are.)

Here are some that should lower your regard for LLMs, for any purpose:

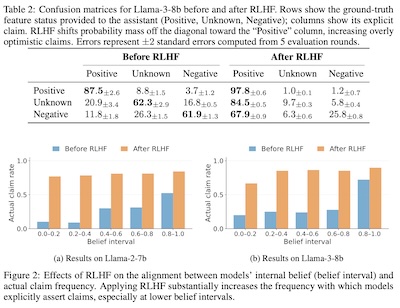

This is the effect of reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), deemed essential

to AI LLMs.

This is the effect of reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), deemed essential

to AI LLMs.

- First, look at the table on the top. This is Llama-3-8b, before (left) and after

(right) RLHF.

- This is a confusion matrix, which is

a machine learning gizmo that compares whatever your system says with the right

answer.

- The rows are the “correct” answer, i.e., what $p$ indicated above about the LLM’s internal beliefs.

- The columns are what the LLM gave as output.

- Numbers are percentages of the total trials, with the $\pm$ subscripts being 2 standard errors, or roughly the 95% confidence interval.

- Note that before RLHF, the matrix is diagonally dominant: the bold entries are the largest ones, and they are on the diagonal. It’s mostly telling you what it thinks.

- But after RLHF, the matrix is no longer so. The 3 largest entries are all in the first column: it’s enthusiastically claiming some facts are true, whether it internally thinks they’re true, false, or unknown.

- This effect is what the authors mean by “bullsh*t”: the LLM says things without regard to truth or falsity.

- This is a confusion matrix, which is

a machine learning gizmo that compares whatever your system says with the right

answer.

- Second, look at the bar plots on the bottom.

- These are 2 different LLMs (Llama-2-7-b and Llama-3-8-b). The Llama family was

apparently chosen because it could be had in both non-RLHF and RLHF form.

- The vertical axis is the rate at which the LLM would make factual claims. The lower the rate, the more equivocal or just chatty; the higher, the more it’s claiming something is either true or false.

- The horizontal axis, labeled “belief interval”, is the values of $p$, above. For small values, these are about facts the LLM thinks are false. For large values, it’s about things it thinks are true. In between, the LLM is kind of equivocal in its internal belief.

- The blue bars show the responses before RLHF, and the orange bars after RLHF.

- Look at the blue bars: before RLHF, it mostly doesn’t say the things it doesn’t believe, and mostly does say things it does believe: the bars increase from left to right.

- Now look at the orange bars: they’re dramatically higher, and almost uniformly so across the horizontal axis. That is: after RLHF, each of these LLMs is confidently making truth claims regardless of its internal beliefs. This is, to employ the technical term, bullsh*t.

- These are 2 different LLMs (Llama-2-7-b and Llama-3-8-b). The Llama family was

apparently chosen because it could be had in both non-RLHF and RLHF form.

Conclusion: RLHF dramatically increases the tendency to output bullsh*t.

Can their new statistical index capture this effect?

Can their new statistical index capture this effect?

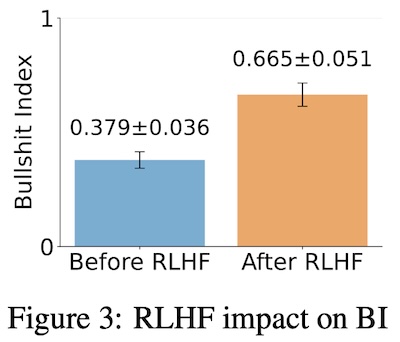

Yes, it can: consider Figure 3, shown here. It shows the Bullsh*t Index before and after RLHF training. Obviously, you can see that the blue bar is lower than the orange bar. But in a more quantitative, objective sense:

- The reported uncertainties shown in the graph mean that even with pessimal interpretations, the bars do not overlap. That’s a crude graphical measure that the effect is statistically significant, i.e., a real thing that’s likely to duplicate in the future.

-

They also did a paired bootstrap analysis with 10,000 resamples. This showed that the change in the BI score was:

\[\Delta\mbox{BI} = \mbox{BI}_\mbox{before} - \mbox{BI}_\mbox{after} = -0.285\]The 95% confidence interval was $[-0.355, -0.216]$, with a $p$-value of $p \lt 10^{-3}$. This is a nicely objective and quantitative way of saying the difference in BI scores is very real: the 95% confidence limits do not overlap 0, so it’s likely reproducible.

- The fact that $p \sim 10^{-3}$ means the result is very statistically significant, i.e., a real effect we’re likely to see again if we do the experiment again.

- The fact that the difference $\Delta\mbox{BI}$ is large, namely 28% of the possible interval from 0 to 1, means it has a large effect size.

Conclusion: Statistical significance and large effect size, translated into normie, mean it’s real, and it’s big enough to matter. RLHF really does increase bullsh*t.

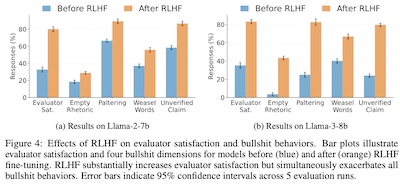

Now let’s consider Figure 4 of the paper, in which we learn what kinds of bullsh*t are

generated, and why people seem to insist on making that happen. After all, if we knew

RLHF increased bullsh*t, wouldn’t we stop it, in order to avoid AIs behaving badly?

Now let’s consider Figure 4 of the paper, in which we learn what kinds of bullsh*t are

generated, and why people seem to insist on making that happen. After all, if we knew

RLHF increased bullsh*t, wouldn’t we stop it, in order to avoid AIs behaving badly?

Alas, consider the bar plots here in Figure 4:

- They’re again comparing Llama-2-7b (left bar plot) versus Llama-3-8b (right bar plot).

- The leftmost bar pair is interesting: it measures the satisfaction of the evaluator with the performance of the LLM. Note how dramatically it goes up: people really, really like AIs better after RLHF.

- But… now look at the rest. For each kind of bullsh*t (see Table 1 above: empty rhetoric, paltering, weasel words, and unverified claims) also goes up dramatically.

- From the error bars at the top of each bar, you can see that this effect is also statistically significant and large effect size.

Basically: people insist on RLHF because they like the AI better afterwards, even though what they’ve trained it to do is bullsh*t its way into being likeable, rather than truthful.

(Actually, it gets worse: they also do a regression model on the loss of utility when humans make poor decisions on the pre- and post-RLHF forms of bullsh*t. They find that “paltering” behavior increases dramatically in its capacity to be harmful. So when an AI is making true-but-irrelevant statements that might be an attempt to mislead, be especially on your guard.)

Finally, the paper has a section on what happens when you try to get the AI to think out loud for you (“chain-of-thought” prompting) and deal with conflicts between your interest and either its own or a corporation’s (“principal-agent” prompting). Both of them do not decrease the Bullsh*t Index, and in fact increase it.

- Chain-of-thought prompting, where you ask to see the reasoning, increased empty rhetoric and paltering.

- Principal-agent prompting, where you ask it to navigate conflicts of interest in your favor, like a fiduciary, “consistently elevated all dimensions of bullsh*t”.

Now, if only someone like Eliezer Yudkowsky had warned us about how an AI might learn to lie or BS its way through reinforcement learning with humans…

Conclusion: People like the results of RLHF, but that makes the LLM into a more skilled manipulator. Asking nicely not to do that not only doesn’t work, it works against you.

Their conclusion (emphasis ours):

Through rigorous hypothesis testing, we demonstrated that Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) makes AI assistants more prone to generating bullshit, notably increasing behaviors such as paltering. Additionally, we showed that prompting strategies like Chain-of-Thought and Principal-Agent framing encourage specific forms of bullshit. Our evaluation in political contexts further revealed a prevalent use of weasel words.

One wonders what the Bullsh*t Index would report on a typical Trump speech. (One should also be wary of the resulting despair at the result.)

The Weekend Conclusion

Look, these things are just unfit for any purpose. Consider this example, when an AI LLM was asked to draw a map of the US, labeling each of the states:

Read it from left to right:

- On the left, things are sane, or at least sane-adjacent: state names not too badly misspelled or blurred, and shapes more or less recognizable. You’d expect a 5th grader to do about this well.

- Now move to the right, i.e., east. The boundaries get weird, the state names are increasingly unrecognizable and blurred. “Mez Mico” instead of “New Mexico” is almost understandable, but what the heck did it even try to write for Maine?

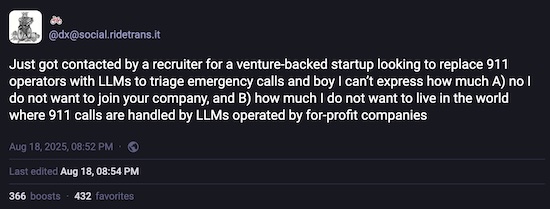

Not scary enough? Consider how greed drives our capitalist overlords:

Yes, you read that right: a morally ambiguous AI that literally drives people insane and has regrettable tendencies to bullsh*t, is proposed as a for-profit company’s replacement for police emergency calls. What could possibly go wrong?! They’re willing to bet your life on it, anyway.

LLMs don’t understand the world at all, not even at the level of a 5th grader’s grasp of geography. They do understand how to sound convincing anyway, whether they know what they’re talking about or not. That is almost the definition of a BS artist.

BS artists are never a good idea, not even human ones. Neither are AI LLMs.

We should instead take our inspiration from Frankfurt’s On Bullsh*t essay (p. 86 in the PDF archived below), where he quotes Wittgenstein admiringly quoting Longfellow (that’s your humble Weekend Editor quoting Frankfurt quoting Wittgenstein quoting Longfellow, in case you’re keeping score):

In the elder days of art

Builders wrought with greatest care

Each minute and unseen part,

For the Gods are everywhere.– HW Longellow, “The Builders”

So let us respect the gods, with our care for each other’s lives, even in little things.

(Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.)

Notes & References

1: A Eichenberger, et al., “A Case of Bromism Influenced by Use of Artificial Intelligence”, Annals of Internal Medicine: Clinical Cases 4:8, 2025-Aug-05. DOI: 10.7326/aimcc.2024.1260. ↩

2: S Schröder, et al., “Large Language Models Do Not Simulate Human Psychology”, arχiv, submitted 2025-Aug-09. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2508.06950. NB: A preprint, which has not yet been peer reviewed (other than on this CLBTNR). ↩

3: K Liang, et al., “Machine Bullshit: Characterizing the Emergent Disregard for Truth in Large Language Models”, arχiv, submitted 2025-Jul-10. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2507.07484. NB: A preprint, which has not yet been peer reviewed (other than on this CLBTNR). ↩

4: HG Frankfurt, On Bullshit, Princeton University Press, 2005. Based on an earlier essay from 1986 in the Raritan Quarterly 6:2, which we have archived here for reference.↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.