Dog Factoring

Tagged:CatBlogging

/

JournalClub

/

Math

/

Obscurantism

/

TheDivineMadness

/

ϜΤΦ

Prime factoring is one of the key algorithms to modern encryption security. Does it help if you use a dog?

Cryptography and the Venerable TM-82

So, cryptography. (No, not “crypto” as in Bitcoin, but good ol’ respectable cryptography, as in sending private messages back and forth.)

Cryptography changed drastically in the late 70s, with the invention of public-key, trap-door ciphers:

- It’s relatively easy to compute the encrypted form of a message from the cleartext, especially since you have the key.

- It’s relatively easy to compute the cleartext of a message from the cryptext, if you have the key.

- It’s insanely difficult to compute the cleartext of a message from the cryptext without the key.

So basically we hope that an encryption function is what’s called a trap-door function: it’s easy to fall through the trap-door (encrypt with key), it’s easy to come back if you know where the secret catch on the trap-door is (decrypt with key), but it’s very hard to come back through the trap-door if you don’t know where the catch is (decrypt without key).

It would be ideal if we could prove decryption was an $NP$-hard function, which is theoretical computer science for something that’s hard to compute, but easy to check the answer. We hope encryption and decryption with key are polynomial time, but decryption without key is at least exponential.

There are no such functions known. That is, we do not have a formal mathematical proof of anything. However, there are heuristic functions that look like this so far, i.e., nobody’s discovered a more efficient decryption step. (For that matter, we don’t even know for sure if $P = NP$ which would make all this collapse and set loose magic in the world. Most knowledgeable people bet that $P \neq NP$, but there are as yet no good proofs. Instant fame if you find one, which is why there are so many crank attempts every year.)

Prime factoring large (hundreds to low thousand decimal digits) integers is one such problem: it’s hard to find the prime factors, but it’s easy-ish to multiply them back to check.

In 1977, Rivest, Shamir & Adelman invented what is now known as the RSA system based

on this. [1] The best factoring algorithms back then, and

indeed now, require time exponential in the number of digits of the integer. (Their

system provides some more interesting features, such as you can publicly disclose an

encryption key to send messages to you, and you can cryptographically sign messages so the

recipients are sure it’s from you. We’ll pass over those aspects for today.)

In 1977, Rivest, Shamir & Adelman invented what is now known as the RSA system based

on this. [1] The best factoring algorithms back then, and

indeed now, require time exponential in the number of digits of the integer. (Their

system provides some more interesting features, such as you can publicly disclose an

encryption key to send messages to you, and you can cryptographically sign messages so the

recipients are sure it’s from you. We’ll pass over those aspects for today.)

RSA showed how to exploit this to make an effectively unbreakable system, using modular exponentiation by repeated squaring. Over the years, we’ve had to make the keys longer and longer as the code-breakers get faster computers, but that’s the thing about an exponential complexity: just a little bit longer key means much harder to break.

The paper starts out with prophetic words:

The era of “electronic mail” may soon be upon us…

Soon, indeed! (Yes, I had an ARPANET email address even back then.)

Still, the US government’s reaction was as paranoid as you might expect: they attempted to declare it retroactively classified, then they declared it a “munition” to prevent its export (in an era when the net was getting started, anything was deemed exported), and even threatened the authors and MIT. [2]

Quantum Computers and Factoring

The RSA algorithm involves picking, in a certain way, a large integer $N$ which is the product of exactly 2 prime factors $p$ and $q$:

\[N = p \times q\]You then (approximately; I’m over-simplifying lots of details here, including conditions on $p$ & $q$, and secure signatures) disclose $N$ publicly so people can encrypt stuff to send to you, but keep $p$ and $q$ secret. They are your decryption keys.

The best factoring algorithms on the best conventional computers are helpless if $N$, $p$, and $q$ are large enough, like several hundred or a couple thousand digits.

People quickly began to suspect that doing polynomial-time factoring would require a

quantum computer, which is a different order of beast from regular computers. Indeed, in

1994 Peter Shor published [3] an algorithm doing exactly

that. (Wikipedia has an explanation

if you don’t want to wade through the paper, but both are really only for fans of math.)

People quickly began to suspect that doing polynomial-time factoring would require a

quantum computer, which is a different order of beast from regular computers. Indeed, in

1994 Peter Shor published [3] an algorithm doing exactly

that. (Wikipedia has an explanation

if you don’t want to wade through the paper, but both are really only for fans of math.)

There were no immediate implementations, as there were no immediate quantum computers. But people started to get nervous. RSA is commonly used in encrypted business, diplomatic, and military communications, at least in the initial key exchange phase. There’s a lot riding on the confidentiality of those, so… nervous.

Now, the quantum computers of the day were (and still are, really) quite small and elementary. So you’d have to start small to demonstrate Shor’s algorithm. That’s what happened:

-

In 2001, Vandersypen and colleagues [4] worked extremely hard to create a quantum computer having 7 qubits total, consisting each of a single spin-1/2 nucleus. Keeping those from thermalizing with the environment and decohering is hard! These nuclei were interrogated with nuclear magnetic resonance techniques, but the system as a whole wouldn’t scale to a larger number of qubits.

Still, they managed to use a quantum computer and Shor’s algorithm to prove:

\[15 = 3 \times 5\]

-

There’s a lot of effort going on here behind the scenes. In order to reduce somewhat the resource consumption, Martín-López and colleagues in 2012 [5] figured out a way to reduce the number of required qubits. Instead of having an $n$-qubit register, they took a single qubit and recycled it $n$ times. The result, as one can see after some math, is about 1/3 the number of qubits required by the more conventional Shor protocol. (Conversely, one could perhaps factor numbers with 3x the digits using the same number of qubits?)

This made their method more likely to be scalable to longer numbers.

Still, given the constraints of their experimental setup, they were able to use a single qubit and – apparently straining mightily – came to the conclusion that:

\[21 = 3 \times 7\]

There were maybe 4 or so other attempts around the same time, but I’ll spare you the details. More modern attempts at quantum computing might be doing better, but it’s still a bit murky to me. (Also, an attempt to factor 35 was made, but failed.)

But before you laugh too much (a little is ok), let me remind you that these are not engineering papers (“Hey, look at this useful thing we made!”). They are, instead, science papers (“Hey, look what’s true about mathematics, quantum mechanics, and nature!”). They demonstrated very impressively that:

- Shor’s algorithm actually works,

- Quantum computing is hard, and

- Scalability in particular is a pain in the rear.

So the RSA prime factors cipher may not be in immediate danger, but the principle has been demonstrated. Now it’s a matter of engineering.

And you know how engineers are.

(Especially when they can pull the rug out from under all the finance people using RSA for encrypted banking transactions. Who wouldn’t like to annoy the finance bros?)

Does It Help If You Use a Dog?

That brings us today’s paper.

That brings us today’s paper.

Everything up to here is prolegomena, setting up the background for The Main Joke. Why bother going through all that just for a joke? As the eminent science writer Martin Gardner said, in his Annotated Alice: Definitive Edition [6], from the introduction to the original Annotated Alice:

But no joke is funny unless you see the point of it, and sometimes a point has to be explained.

So now that you know at least the bare bones about RSA ciphers, factorization algorithms, and the danger to them posed by quantum computers… you’re prepared to joke about them in the proper fashion!

Gutman & Neuhaus [7] have written a very silly paper to

make a very serious point: most of the demonstrations of factoring with quantum computers

have either been physics experiments not yet relevant to cryptography, or have been pretty

much rigged to look more impressive than they really are.

Gutman & Neuhaus [7] have written a very silly paper to

make a very serious point: most of the demonstrations of factoring with quantum computers

have either been physics experiments not yet relevant to cryptography, or have been pretty

much rigged to look more impressive than they really are.

The ‘Physics Experiments’

Some of the factorizations of ridiculously simple integers like the above are mostly about physics experiments of various sorts, say, maintaining quantum coherence in a system of nuclear spins. They demonstrate the feasibility of quantum computing by doing Shor’s algorithm on a trivial case.

As a physics experiment, this is fine and noble. As a claim about RSA crypto security, they are ridiculous. Most such claims were not made by the experimenters, but added by credulous media.

The ‘Stunt Factorizations’

Nevertheless, people can’t resist “stunt factorizations”, in which the problem has been carefully prepared to have hidden structure to exploit and factorize on trivial amounts of hardware. (Analogous, the authors say, to the “force decks” used in card tricks that look like a full deck of cards, but really contain only one or two.)

-

For example, if $N = p \times q$ where $p$ and $q$ are prime, but differ only in a few bits, then $N$ can be factorized by integer square root and brute-force search.

No real-world RSA system would allow such an $N$, but this inconvenient fact is seldom mentioned.

-

Another example is the factorization of 1,099,551,473,989 which in binary begins with 100000000000000… thereby hinting that a game of some sort is afoot.

Another such game might be jokingly termed Callas Normal Form, after Jon Callas who pointed it out. Here, if $n \le m$:

\[\left\{ \begin{align*} p &= 2^{n} - 1 \\ q &= 2^{m} + 1 \end{align*} \right.\]then $N = p \times q$ begins in binary with $n$ 1 bits, then $m-n$ 0 bits, and ends in $n$ 1 bits. At that point, factorization proceeds more via hijinks than by cleverness.

Again, this is a case no real-world RSA toolkit would generate.

There is a paper out this spring and published this summer from a Chinese group claiming to have used a D-wave quantum computer to solve RSA-2048: factorize 2048-bit $N$ values into pairs of primes $p$ and $q$. [8]

In words attributed to HL Mencken: “Interesting, if true.”

However, according to Gutmann & Neuhaus, all the examples in the paper are “sleight-of-hand” numbers. They were specially chosen so that $p$ and $q$ differ by either 2 or 6. So it’s perfectly reasonable to take the integer square root of $N$ and search nearby! In slightly more detail:

- There exists a 1024-bit integer $x$ halfway between $p$ and $q$.

- There exists an integer $d$ such that $p = x - d$ and $q = x + d$.

- The only choices allowed for $d$ are 1 and 3, depending on whether $|p-q|$ is 2 or 6, respectively.

So $N = pq = (x-d)(x+d) = x^2 - d^2$, so $N + d^2 = x^2$ must be a perfect square. If $d$ is either 1 or 3, just try $d = 3$ and see if it’s a perfect square:

- Let $x$ be the integer square root of $N + 9$ and $r$ be its remainder.

- If $r = 0$, then $d = 3$, so the factors are $x-3$ and $x+3$.

- Else if $r = 8$, then $d = 1$, so the factors are $x-1$ and $x+1$.

- Else the problem is not one that has been rigged for you in advance (or at least not in this fasion).

These tricks are common. As the authors say:

So far as we have been able to determine, no quantum factorisation has ever factorised a value that wasn’t either a carefully-constructed sleight-of-hand number or for which most of the work wasn’t done beforehand with a computer in order to transform the problem into a different one that could then be readily solved by a physics experiment [23] [10].

The VIC-20 8-bit CPU

Just to rub in the point, the authors show this can be done on a consumer-class computer from 1980: the Commodore VIC-20.

This used a 6502 processor (introduced in 1975, which I first encountered in about 1976 or 1977), with:

- 3 registers of 8 bits each,

- a data bus 8 bits wide, and

- a 16 bit address space.

Typically configured the VIC-20 had 20kb of ROM and a mere 5kb of RAM. But only 3.5kb of the RAM was available to users, the rest being taken up with system stuff. The clock speed was a glacial 1MHz. (I remember when the Zilog Z-80 came out, at a blistering 5MHz. That’s a mere factor of 1,000 slower clock speed than computers of today. Given pipelining and other architectural parallelism tricks, modern hardware is much faster even than that.)

The small cases of $15 = 3 \times 5$ and $21 = 3 \times 7$ were done with lookup tables. The integer square root with remainder algorithm descends from one written by no less a luminary than John von Neumann himself, for the EDVAC vacuum tube computer in 1945.

They wrote some code in 6502 assembler, and ran it on an emulator. The paper points you to where to get the code, if you’re interested.

- The code was 427 lines long.

- The ROM image had 794 code and data bytes, 256 were for the number to be factored.

- The code required 1792 bytes of RAM, which fit easily.

Notably, no multiplication or division operations were required, which is good because the 6502 didn’t have that, much less for “bignum” integers with 2,048 bits!

Results: They replicated all 10 results from the D-Wave paper, each taking about 16.5 seconds if one took the number of clock ticks and divided by 1 MHz. Running it on a modern laptop took less than a second each.

Conclusion: The results reported in the D-Wave paper are trivial, since the examples were chosen via sleight-of-hand to be easily solved.

The D-Wave paper’s authors showed subtle comic taste in their choice to publish this joke, which I admire & applaud. However, they did not honestly admit to having done so, which I deplore: jokes are only funny if you let people in on the joke!

The Abacus

Given that the above-referenced integer square root algorithm was inspired by integer

square roots on an abacus, you can probably guess what comes next.

Given that the above-referenced integer square root algorithm was inspired by integer

square roots on an abacus, you can probably guess what comes next.

They “implemented” the $15 = 3 \times 5$ and $21 = 3 \times 7$ factorizations on an abacus. Though, really, since this is done one digit at a time using the user’s memory as a buffer, there was nothing left for the abacus to do.

This is not (entirely) silly: it points up the triviality of implementation, meaning the physics experiments doing this were about physics, not cryptography.

The rest, though, is entirely silly.

They pointed out that to replicate the D-Wave paper’s factorization of a (sort of) RSA-2048 integer, they’d need 616 digits. Each column of an abacus is one digit, and they come typically in 9, 11, or 13 digit versions. Clearly some work on abacus hardware is required in order to continue the joke:

In fact the size of a 616-digit abacus is unpleasant to contemplate, so we leave the construction of such a bignum abacus to the reader, or perhaps an enthusiastic woodworking hobbyist with a YouTube channel.

Sounds about right to me.

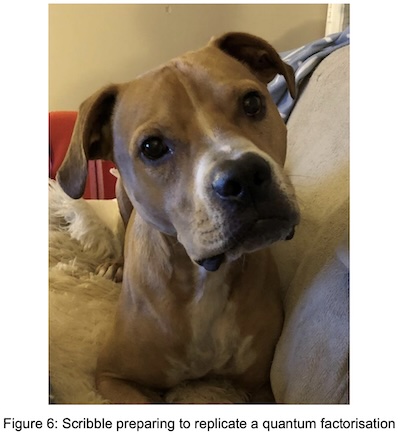

The Dog

In order to further replicate the quantum factorizations of 15 and 21, they employed a

‘recently-calibrated reference dog, Scribble’, shown here.

In order to further replicate the quantum factorizations of 15 and 21, they employed a

‘recently-calibrated reference dog, Scribble’, shown here.

This fine animal is apparently so well-behaved that in general he does not bark. However, upon vigorous play, he has been trained to bark 3 times:

Having him perform quantum factorization required having his owner play with him with a ball in order to encourage him to bark. It was a special performance just for this publication, because he understands the importance of evidence-based science.

Good dog!

He apparently failed at factoring 35, because he had learned to bark 3 times. That’s ok, the first quantum factoring attempt on 35 failed, too.

The RSA-2048 candidates proposed in the D-Wave paper were deemed beyond the scope of this dog.

No dogs were harmed in the course of this research:

According to most Codes of Ethics, Scribble’s contribution to this paper does not rise to the level where he is required to be listed as co-author. However since he was a participant in the work rather than the subject of an experiment his contributions are exempt from review board approval.

In fact, as far as reproducibility of this research, they correctly note one difficulty:

Finally, the apparatus for the canine-based factorization may be obtained from any animal shelter. Although our experiment used a Staffy, almost any dog breed should be suitable, although smaller yappy dogs may over-report values.

The Point

Almost all the reports of quantum factorization are either notable as physics experiments as yet irrelevant to cryptography, or as “stunt factorizations” using sham keys that no RSA cryptography system would permit.

The authors present several sensible criteria for factorization claims going forward. They’re about what you think:

- the factors should be chosen sensibly by the criteria used in cryptography (of which there are several),

- the experiment should be blinded (the factoring researchers are not permitted to know the number in advance, nor the solution until they find it), and

- the process should be repeated on 10 different values chosen independently from the experimenters, to show reproducibility.

The real question to me is: How do papers like the sham factorizations and the sleight of hand D-Wave paper get published? Shouldn’t at least one of the referees have some cryptography background to check for things like this? Shouldn’t there be a standard registry of appropriately chosen factoring problems, whose solutions are not revealed until someone solves them?

The thing about common sense is that it’s so uncommon!

Chicken

Sometimes, when reading a deliberately silly paper, one should calibrate it against The Standards.

One such standard is Doug Zongker’s famous “Chicken” paper & talk [9], from 2006-2007. Though published in the venerable Annals of Improbable Research, it was actually presented at a AAAS conference in 2007 (admittedly in the humor section, which is only fitting).

He mocks the form of a technical talk, without having the least bit of content. He shows many graphs, tables, and equations – all without meaning. He only says the word “chicken”, though with tone of voice to emphasize Very Important Points about chickens.

Be sure to stick around for the end of the video, when during the question period, someone asks a question using only the word chicken… and Zongker has a pre-prepared response slide just in case somebody did that. Now that’s preparedness surrealism!

The Weekend Conclusion

Dog factoring is not really a thing, of course, beyond satire. (Though it is good

satire!)

Dog factoring is not really a thing, of course, beyond satire. (Though it is good

satire!)

But at Chez Weekend, we’re less dog-folk and more cat-folk. So far, attempts to get the 2 cats to factorize integers have been unsuccessful.

Still, there are a few members of family Canidae frequenting the Château Weekend grounds and gardens, shown here. It appears to be a wild fox, though a bit skinny. We’ve seen several of them running around the garden, playing cutely. They seem to have gotten control of the enormous rabbit population, and the otherwise adorable-but-ignorable chipmunks. The wild turkeys, several times fox-sized, are unlikely prey but still spooked. (Wild turkeys can fly, just… not very well.)

As you can see here, the Weekend Publisher (and the Assistant Weekend Publisher, not shown) disapproves of dogs of all sorts, August dies caniculares or not. (His opinions on factoring are as yet unknown.)

But all of us here are agreed: Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.

Notes & References

1: R Rivest, A Shamir, L Adleman, “A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems”, MIT Laboratory for Computer Science (now part of CSAIL), Technical Memo LCS/TM 82, April 1977. ↩

2: A couple weird stories:

-

In the summer of 1977, the RSA algorithm was discussed in Scientific American, in Martin Gardner’s famous “Mathematical Games” column. I was an avid reader of that column in those days, and since I was entering MIT in fall 1977 as a physics grad student, I thought I’d pick up a copy of TM-82 for recreational reading.

When I went to the publications office to ask for one, I got a deeply suspicious look, and questions like: “Are you an MIT affiliate?” And: “What are you going to do with it if I give it to you?” All very weird, but it turned out the Institute was fighting the US government in its effort to strangle the whole thing, and had temporarily stopped giving it out.

I thought I looked like a scruffy grad student and not a spy, but whatever.

But… they helpfully added that I could put my name on a waiting list to get it “when things clear up”. Being young & naïve, I did so.

Eventually, I got the paper, after maybe 3-4 months.

But in the meantime, some weird stuff happened, since I was apparently now on some very weird lists. I had a girlfriend in those days (yes, that’s weird too, given my lack of social skills, but it’s not the weird part of this story), whom I would call periodically long-distance (also a weird thing of those bygone days).

Then one day her dormitory phone wouldn’t connect. She eventually got it repaired by her university, but the repair guy said there was a part missing. Apparently somebody had entered her room, taken the phone apart, decided it was too old to mess with, and put it back together incompetently.

Was that a probable attempt at bugging her phone, related to my wanting a copy of an encryption paper? Sure feels like it!

So maybe in some FBI/CIA/DSA database, there’s an entry about me from September 1977.

-

On the subject of old phones: MIT had a system called “dorm-phone”, which was ancient. It didn’t really connect to the outside world, only to Institute phones. It was run through a relay rack in the basement of my graduate dorm. You could go down there and stand outside the door to the phone equipment room, hearing the relays go “clacketa-clacketa”.

Years later, a colleague told me a weird phone story of when he first arrived at MIT.

Seeing the ancient dorm-phone in his room, he correctly guessed that he could do hook-flash dialing: you rhythmically tap the hang-up buttons on the hook, with a short pause between digits. Like the 20mA current loop machinery in the dial, this feels to the phone switch like the rotary dial sliding over the contacts. So he made a quick call to a friend in the dorm, smiled at the oddity, and hung up.

A moment later, his phone rang. The conversation went like this:

Mysterious angry voice: Does your phone have a dial on it?!

My colleague: Uh… yes?

Mysterious angry voice: Then use it! (hangs up)Somebody had been in the relay room at the time, and heard the relays not going gently “clacketa-clacketa”, but “SLAM! SLAM!”. This sort of thing is hard on those ancient relays, so he worked back from the relays to the source number and expressed his fervent desire that this abuse should come to an end. (Possibly a Bad Word might have been used.)

My colleague then realized that as a 70s-era phone hacker, he was far from unique in that environment. ↩

3: PW Shor, “Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring”, Proc 35th Symp Fndns of Comp Sci, 1994-Nov. DOI: 10.1109/SFCS.1994.365700. ↩

4: LMK Vandersypen, et al., “Experimental realization of Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance”, Nature 414:6866, 2001-Dec-20, pp. 883-887. DOI: 10.1038/414883a. PMID: 11780055.

There is an unpaywalled pre-print available at arXiv:quant-ph/0112176. ↩

5: E Martín-López, et al., “Experimental realization of Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm using qubit recycling”, Nature Photonics 6, 2012-Oct-12, pp. 773-776. DOI: 10.1038/nphoton.2012.259.

There is an unpaywalled pre-print available at arXiv:1111.4147. ↩

6: M Gardner, The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN-13: 978-0393048476.

The quote appears on page xiii of the introduction in my edition.↩

7: P Gutmann & S Neuhaus, “Replication of Quantum Factorisation Records with an 8-bit Home Computer, an Abacus, and a Dog”, Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2025/1237, version of 2025-Jul-19.

NB: The authors carefully explain one of their notational choices in footnote 1:

We use the UK form “factorise” here in place of the US variants “factorize” or “factor” in order to avoid the 40% tariff on the US term.

Just so you know what to expect, going in. (Fair enough, though? I like these guys. I mean, I really like them.) ↩

8: C Wang, et al., “A First Successful Factorization of RSA-2048 Integer by D-Wave Quantum Computer”, Tsinghua Science and Technology 30:3, p. 1270, 2025-Jun. DOI: 10.26599/TST.2024.9010028.

NB: As Gutmann & Neuhaus wryly note:

We note that the paper has, at the time of writing (March 2025) a publication date in the future (June 2025). It appears that the D-Wave device can also shift time and relative dimensions in space.

9: D Zongker, “Chicken Chicken Chicken: Chicken Chicken”, Annals of Improbable Research 12:5, 2006-Sept/Oct.

NB: Originally published in the AIR in 2006, but later delivered at the Improbable Research session at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), in San Francisco, 2007-Feb-16. Video documentation is by Yoram Bauman.

The formal paper is here, replete with graphs, tables and equations. Deeply impressive satire. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.